In addition, it was for centuries both home for a community of Benedictine monks and seat of the mighty Prince Bishops of Durham.

Who, having visited Durham Cathedral, can doubt that it is one of the most glorious buildings in Christendom? In his classic two-volume work entitled Byzantine and Romanesque Architecture, T.G. Jackson wrote:

The exterior of Durham, with its three massive towers, its enormous bulk and its superb position on a rocky promontory round which the river Wear sweeps in a grand wooded defile, makes it perhaps the most impressive picture of any cathedral in Europe.

The cathedral building – a large part of which dates back some 900 years – is widely regarded as one of the most complete and perfect examples of Romanesque architecture in existence. It possesses a heroic grandeur that moved Sir Walter Scott to write:

Yet well I love thy mixed and massive piles

Half church of God half castle ‘gainst the Scot

And long to roam these venerable aisles

With records stored of deeds long since forgot

Yet, above and beyond its physical presence, the Cathedral and its setting have an ethereal quality captured by William Noel Hodgson in these lines penned in the trenches where he was to die on 1 July 1916:

Above the storied city, ringed about

With shining waters, stands God’s ancient house

Over the windy uplands gazing out

Towards the sea; and deep about it drowse

The grey dreams of the buried centuries,

And through all time across the rustling weirs

An ancient river passes; thus it lies,

Exceeding wise and strong and full of years.

Perhaps, though, the true magic of Durham Cathedral lies in its ability to evoke a whole range of powerful emotions in the visitor simultaneously. The celebrated, nineteenth century American novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne, for example, recorded in his English Notebooks:

I paused upon the bridge, and admired and wondered at the beauty and glory of this scene…it was grand, venerable, and sweet, all at once; I never saw so lovely and magnificent a scene, nor (being content with this) do I care to see a better.

In 1986, the uniqueness of this religious and cultural treasure was recognised when the Cathedral, together with Durham Castle, was awarded the highest of accolades – designation as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Durham Castle

As the threat from the Scots receded, the Castle evolved into an impressive yet comfortable palace for Durham’s all-powerful Prince Bishops. Then, in 1837, it was handed over for the use of the newly-founded University of Durham. At first, the Castle contained the entire University. Soon, though, the rapidly-expanding University needed more space. So finally, Durham Castle became University College, Durham – a residential community for generations of both dons and students.

For a complete guide to Durham Castle, take a look at our dedicated things to do in Durham guide.

St Oswald: Warrior King and Martyr

Following the death of Edwin in battle in 633, Oswald returned to Northumbria and was crowned king of Northumbria. In 635, he defeated and killed Cadwallon, King of the Welsh, at the battle of Heavenfield just north of Hexham. Oswald persuaded one of St Columba’s disciples – St Aidan – to move down from Iona in order to found a monastery at Lindisfarne – an island off the coast of Northumbria. From this new base, St Aidan set about converting Oswald’s subjects to Christianity with the king’s blessing.

Oswald is not just notable for his religious influence, however. St Bede, in his great chronicle the Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation, claimed that Oswald established himself as overlord of the almost the whole of England during his reign. In 642, Oswald was killed at the battle of Maserfeld near Oswestry by the pagan King Penda of Mercia who then ordered the body of his adversary to be dismembered. Oswald’s head, however, was recovered and sent to the monastery at Lindisfarne where it became a holy relic.

During the Viking raids of 875, the monks of Lindisfarne fled for safety. They carried with them St Oswald’s head together the monastery’s other great treasures such as the body of St Cuthbert and the Lindisfarne Gospels. Eventually, the descendants of the Lindisfarne monks founded a great new monastery at Durham where the head of St Oswald – buried in St Cuthbert’s tomb – remains to this day.

Oswald was canonised some fifty years after his death. His feast day is 5th August.

St Cuthbert the Wonder-worker

Cuthbert was born in 635 near Melrose in Scotland of humble parentage. As a boy, he tended sheep on the hills in that area. In the year 651, while watching his sheep, he saw a vision. St Bede in his Life and Miracles of St Cuthbert, Bishop of Lindisfarne describes what Cuthbert observed thus:

On a sudden he saw a long stream of light break through the darkness of the night, and in the midst of it a company of the heavenly host descended to the earth, and having received among them a spirit of surpassing brightness, returned without delay to their heavenly home.

Next morning, he found that St Aidan – founder of the Priory of Lindisfarne and a man of great holiness – had died at the very moment of his vision. At this point, so St Bede claims, Cuthbert gave up being a shepherd and decided to enter the Celtic monastery of Melrose in order to train as a monk. There he soon became known for his piety and learning. In due course, he went to Ripon to help found the monastery there. Expelled when he refused to accept the Roman monastic traditions urged upon him, Cuthbert returned to Melrose where he was appointed Prior in 661.

In 664, the Synod of Whitby decided in favour of the Roman monastic traditions. Cuthbert accepted that decision. He was then appointed Prior of the great monastery of Lindisfarne, in order that he might introduce the monastic changes to that house. The fact that he himself had been trained in the Celtic tradition and was now conforming to the new order helped him to persuade the monks at Lindisfarne to accept the change themselves. Cuthbert remained Prior a Lindisfarne until 676, when he retired to the nearby island of Inner Farne in order to live the life of a hermit.

Here Cuthbert spent his time in prayer and contemplation having only the seals and sea birds for company. However, he reluctantly agreed to accept appointment as Bishop of Lindisfarne in 685. Despite this reluctance, he threw himself energetically into his new role travelling widely and converting people to the Christian faith. Two years later, though, he retired from the post of Bishop and returned to his island hermitage where he died in 687. Cuthbert’s body was carried back to Lindisfarne and buried there, in accordance with his wishes.

The Legend of St Cuthbert

In 698, Cuthbert’s tomb was reopened and it was discovered that his body had not corrupted in any way. He was then reburied, this time in an oak coffin covered with simple, but beautiful carvings. The remains of this coffin can be seen in the Cathedral Treasury. Almost immediately, his tomb was associated with miracles. Indeed, these were so numerous that Cuthbert became known as the Wonder-worker of England. As a result of these miraculous occurrences, he was canonised.

During a rest at Durham, tradition says that Cuthbert appeared in a vision to the monks charged with carrying his body. He indicated to them that he wished his final resting place to be at Dunholme – the location of which they discovered by overhearing a milkmaid say that it was the place where her lost cow had strayed.

This site – Durham Peninsula – also had the benefits of being both easily defended and having ample supplies of fresh water. So, here St Cuthbert’s remains were finally laid to rest, first in a rough wooden chapel, then a fine Saxon stone church. This church – called the White Church – was dedicated in 998. However, in 1093, the Norman conquerors began to dismantle the White Church and to replace it with the present magnificent Cathedral. Cuthbert’s remains – together with the head of the warrior king St Oswald – were placed in a specially built shrine in the new Cathedral in 1104. At this time – when Cuthbert had been dead over 400 years – his coffin was opened again, and his body was found to be still uncorrupted.

Throughout the Middle Ages, Durham was one of the most important pilgrimage centres in England, and Cuthbert its most famous saint. In 1540, during the Reformation, King Henry VIII sent commissioners to destroy Cuthbert’s shrine. A later account of what then happened, states:

After the spoil of his ornaments and jewels they approached near his body, expecting nothing but dust and ashes: but, perceiving the chest he lay in strongly bound with iron, the goldsmith broke it open, when they found him lying whole uncorrupt with his face bare, and his beard as of a fortnight’s growth, and all the vestments about him as he was accustomed to say mass.

The monks were allowed to bury him on the ground under the dismantled shrine. This tomb was reopened in 1827, at which time a skeleton, together with another adult skull – presumably that of St Oswald – was found. The skeleton was swathed in beautiful but decayed robes and was wearing a gold pectoral cross inlaid with garnets. A photograph of the pectoral cross can be seen above. The designs of these items matched the descriptions of those found in 1104. However, some have argued that the real body of St Cuthbert had been secretly removed by Benedictine monks during the Reformation and buried elsewhere. St Cuthbert’s feast day is 20th March.

Durham’s Benedictine Monks

Bishop Carileph (1081-1096) – who himself had been a monk – founded the great Benedictine Monastery of Durham in 1083. This was ten years before he ordered construction of the present Cathedral to begin. The new community of monks replaced the descendants of the Lindisfarne monks as guardians of the tomb of St Cuthbert. Benedictine monks were also known as ‘Black Monks’ because of the colour of the habits that they wore.

They followed the ‘Rule’ or way of life proposed by St Benedict of Nursia – a sixth century Italian monk who is regarded as the father of Western monasticism. Although the Rule of St Benedict demanded poverty, chastity and obedience, it also provided for adequate food, clothing, and shelter. Monks were not required to take a vow of silence, although they were expected only to speak when necessary. By the standards of the time, the Rule of St Benedict was relatively humane – which may explain its popularity!

The Monastery of Durham was one of the richest in England. The community of around forty monks and six novices was led by a Prior – the Bishop nominally holding the more senior rank of Abbot. Each day, the Prior and the monks would meet in the Chapter House to hear a chapter read from the Rule of St Benedict and then to attend to the business of running the Monastery.

The monks lived a highly ordered existence. On a typical day, they would spent nine hours working, two hours studying, one hour eating meals and seven hours asleep. The remainder of the day was taken up with meditation and prayer. Work involved such activities as writing or copying manuscripts, administering the monastery or its estates, and running e.g. the infirmary, the guesthouse or the almshouses.

While at the Monastery, each monk was expected to attend as many as seven religious services each day. Matins was celebrated at midnight – in Summer, the start of the monastic day. Then came a series of five short services that punctuated the daylight hours. Prime was celebrated before breakfast at 6 am (the first hour), Terce at 9 am (the third hour), Sext at noon (the sixth hour), None at 3 pm (the ninth hour), and Vespers before supper. Finally, Compline was celebrated shortly before the monks went to bed.

After King Henry VIII quarrelled with the Pope, he broke with the Roman Catholic Church. Following this, he ordered that the monasteries in England be dissolved and that all their estates and other wealth be confiscated. So, from 1540 – after more than 450 years of existence – the Benedictine monastery at Durham was abolished. However, the change may not have been that dramatic at first. The Monastery was refounded as the Cathedral Church of Christ and Blessed Mary the Virgin shortly afterwards. The last Prior – Hugh Whitehead – became the first Dean and twelve of the monks became the first canons of the Cathedral.

St Bede the Scholar Monk

St Bede – also known as the Venerable Bede – is widely regarded as the greatest of all the Anglo-Saxon scholars. He wrote some forty books on practically every area of knowledge, but most of his writing was on theology and history. He wrote of himself:

I have devoted my energies to the study of the scriptures, observing monastic discipline, and singing the daily services in church; study, teaching, and writing have always been my delight.

Bede’s biblical writings were extensive and important in their time, but it is as an historian that he is best known. His most famous work is the Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation, a chronicle of English history from the Roman occupation until the date of its completion in 731. Even today, this work is still considered an important source of early English history. He also wrote grammatical and chronological works, hymns, letters and homilies, and compiled the first martyrology.

It is said that, at one stage, Bede was pressed to become prior of the monastery. He declined, however, fearing that this task would distract him from his scholarly calling.

During his last illness in 735, Bede was working on a translation of St John’s Gospel. Unable to write himself, the 62 year-old scholar had to rely upon a young scribe called Wilbert for assistance. According to one account, this final conversation took place between them:

Dear master, there is still one sentence that we have not written down.’ Bede responded, ‘Write quickly.’ After a little while the boy said, ‘There, now it is written.’ ‘You have said well.’ replied Bede, ‘It is at an end. All is finished.

Moments later, surrounded by the monks amongst whom he had lived, Bede offered up a last prayer and then died. His only possessions – some handkerchiefs, a few peppercorns and a small quantity of incense – were divided amongst his brother monks, as he had previously directed.

In about 1022, Bede’s remains were taken – some say stolen – from Jarrow by a monk called Alfred, and brought to Durham. At first, they were buried in the Choir together with the remains of St Cuthbert. Then, in 1370, Bede’s bones were moved to a splendid shrine in the Galilee Chapel. This shrine, however, was destroyed in 1540 during the Reformation and Bede’s remains were buried in a grave where the shrine had previously stood. When the grave was opened again in 1831, some bones and a gilded iron finger-ring were found. The bones were re-buried and the present tomb erected above them. The ring is now in the Cathedral’s Treasury Museum.

Bede was declared venerable by the church in 836 and was canonised in 1899. His feast day is May 27 – the day that he died.

Durham’s Prince Bishops

The first Norman kings realised that – because it was so remote from their power based in the South – the North-East of England was particularly vulnerable both to rebellion by the local Saxon population and to invasion by the armies of Scotland. Shortly after the Norman Conquest, therefore, William the Conqueror appointed Bishop Walcher of Durham (1071-1081) Earl-Bishop of Northumbria. This appointment concentrated both secular and spiritual power over the whole of the North-East of England in the hands of one person.

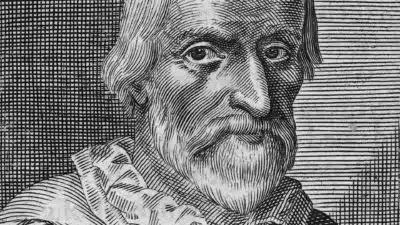

Following Walcher’s murder by an angry mob in Gateshead in 1081, the king decided to continue with this policy, but in a more limited way. So, he elevated Bishop Carileph (1081-1096) – and subsequent bishops – to the rank of Prince Bishop, giving them vice-regal power over an area that became known as the Palatinate of Durham. The Palatinate covered much of the modern counties of Cleveland, Durham and Tyne & Wear together with parts of the county of Northumberland. The secular power the Prince Bishops is well symbolised by the illuminated letter from the bible of Bishop Pudsey (1153-1195) pictured above.

A century later – boasting of the power of his master – the steward of Bishop Bek (1284-1310) claimed:

There are two kings in England, namely the Lord King of England, wearing a crown in sign of his regality and the Lord Bishop of Durham wearing a mitre in place of a crown, in sign of his regality in the diocese of Durham.

This was no idle boast, however. The Prince Bishops had the similar royal powers within the Palatinate to those that the King exercised in other parts of his Kingdom. Not only did they have their own Parliament – Durham sent no representatives to London – but also they could raise their own armies, levy their own taxes, mint their own coins and set up their own court system. At the high point of their powers, the Prince Bishops could even enter into negotiations directly with the Kings of Scotland, create their own barons and regulate commerce by granting charters for markets and fairs.

Bishop Van Mildert (1826-36) – the last of the Prince-Bishops – was involved in founding the University of Durham in 1832. Durham Castle, which had always been the principal stronghold and palace of the Prince-Bishops, was handed over in 1837 to provide a home for this fledgling institution. Since then, the main seat of the Bishops of Durham has been at Auckland Castle, just a few miles south of Durham.

It was only with the death of Bishop Van Mildert in 1836 that the secular powers of the Bishops of Durham were finally surrendered to the King. Interestingly, though, the Palatinate court system survived for almost another century and a half. Not until 1971 was the system finally merged into the English court structure – exactly 900 years after William the Conqueror appointed Bishop Walcher Earl-Bishop of Northumbria!